Wacky Races

Making Crazy Town a tourist destination again.

Here’s the thing about [visiting] Crazy town; There’s a lot of pictures, but you don’t really do anything.

- Dave Razowsky

One of the unfortunate side effects of fun-loving improv (Yes Anding ideas, putting a lot of verve and ideas into the pot, just really letting loose), is it can all end up a little nuts. You end up in Crazy Town, and once you’re there it’s hard to get out. Call it the arrow of entropic improv. I liken it to Pink Elephants on Parade from Dumbo. A lot of fun stuff, but altogether it’s a loud lawless frightening mess.

But what if it worked? What if 10 pounds of ideas in a 2 pound bag was good value, instead of a burst mess you have to clean up.

Because sometimes it does.

Sometimes, instead of Crazy Town, you get Wacky Races.

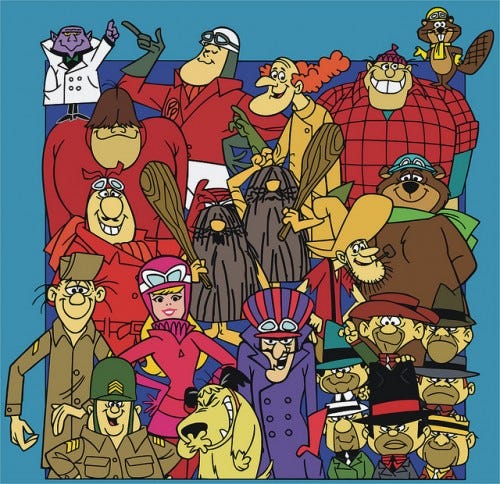

On Wacky Races, things were wacky. We have cavemen and gangsters and impossible cars and blatant cheating. Crazytown, you might say. But Wacky Races works.

Why?

Rule One: It has a Rock-Solid Base Reality.

This might come as a surprise. Wacky Races is as cartoony as they come. The laws of physics seem to get broken all the time, and they’re not even the same laws every time (compared to say the rules of the Road Runner universe). There is no straight character (such as Alice in Alice in Wonderland) to reassure this is indeed unusual. In Wacky Races, you have absurd characters interacting with other absurd characters within an absurd world, so how can you tell what is normal? How can you trust anything? What is our base reality?

They are in a race, and they are competing.

Every episode, every time. They might have different reactions to the winning (Dick Dastardly cares too much, most are just here for the kicks) but they definitely stick to that iron thread. It’s in the title, that’s all we need. Wacky is also in the title, so if we have nothing else we’d chalk it up to that. It is what they will be doing, it is what we are watching, we are therefore not confused. If Dastardly gets a job as a mail man and adopts three gorgeous blonde kids, it better relate back to the race good and sharpish. When Dastardly wanted to stop a pigeon instead stop his competitors, we got Dastardly and Muttley in Their Flying Machines. Likewise, if you want to change your game, start a new scene.

Rule Two: A Racetrack Has an Obvious Path.

You can take the train to Crazy Town, but you have to take the local — Neil Casey

We need to see every stop, how you got there, and why. Why is Crazy Town like that. The scene in Cabin in the Woods where all the creatures, from every horror world, are loose and bloodthirsty, is only made possible because we saw the compound, got explained their purpose, and saw the break out.

That’s the ideal. But it doesn’t happen every time. Wacky Races does not open with us following the origin story of each player, how they got so wacky, and why they got so enthusiastic about racing. That would be a lot. If your scene can’t show why these crazy elements exist, we will accept an explanation why these crazy elements are here. A shared task, shared goals, shared values, can tie seemingly disparate weird details just as well as a shared origin. Banana, strawberry and watermelon are very different but we clearly see their origin (fruit) as a defining trait. The priest, the Irishman and the blind piano player all walked into a pub for the same reason, they have a shared goal.

Rule Three: The Balance of Good and Evil, Right and Wrong, Remains Intact.

For me, what really makes a scene go to crazy town is not the wacky details, but the lack of reactions. If you treat everything as normal, the same, then we expect you to explain why. You can help yourself and your scene by simply providing the light and shade, the straight line.

But hang on, didn’t we say Wacky Races had no straight character?

We did. But it does retain a sense of morality, a straight clean virtuous line to replace the straight character to foster audience surrogacy. In this case, the near-do-wells never succeed. Not just at the end of the episode, but systematically through-out. This is the law of the world we know it (or wish to believe anyway).

Now does good need to vanquish over evil in your scene? Not necessarily, bad guys can win. But if someone is good the audience wants to know, and if someone is bad the audience wants to know. That certain actions create certain responses in characters (someone being shouted at reacts as if that is happening, if someone’s sad they cry), and if those responses are subverted it is treated as an subversion not just ignored. This is how the real world works, a world of equal and opposite reactions, and therefore is crucial in establishing Crazy Town as Crazy Town, Planet Earth at least.

Rule Four: Stereotypes are Real

No, they’re not

Yes, they are.

The Wacky Races competitors are blatant adopted stock characters fresh from the 1930’s (even that’s generous: Red Max is a WWI dog-fighter, and Dastardly is damsel-on-the-rails melodrama). Their names, their dress, their vehicles, even their special abilities all stem from their stereotype.

How does this kind of type-casting help us navigate crazy town?

Because it’s familiar, and familiarity we need.

Stock characters, stereotypes, can packaged with a context and justification (two key improv words).

Shooting a gun into the air is arresting in any context (and if its not, check your map, because you might just be in Crazytown) but there is a difference between a cowboy doing it (familiar) and a nun, or a witch, or even a living loaded gun.

A living loaded gun might not be the stock character of nuns or witches, but whatever preconceptions of their traits I have (angry, likes loud noises, male probably), having his own gun wasn’t one I was expecting. Too many unchecked elements like that and there is too much new normals for the average Joe to both process and laugh contently.

In a sitcom (like Wacky Races), you are tuning in to how character type A (caveman or brute or Homer Simpson) interacts with character type G (heiress, or the princess, or Rachel from Friends) in a given situation (having a wacky race).

Familiarity makes things less surprising. Which is a good thing. In a town called Crazy where everything is surprising, the solid ground of predictability is a godsend. You’re lost in Crazytown, but thank God every town has a McDonald’s.

Context and Justification also keeps your characters as wacky (eccentric), and away from crazy (certifiably ill). This is only partially relevant to the Crazy Town problem, but if your interested I’ve talked about the problems with ‘crazy’ characters in far more detail here.

Rule Five: A Race has a Finish

In Crazy Town, the town stays still; it’s a town. In a Wacky Races scene, it moves. Room to breath. Something is happening.

This point is a little more abstract, and in explanation some of the points already made might be repeated, but here we go.

I believe in a scene a lot of the comedy comes periodically bending how the scene will end. Maybe this is obvious, the element of surprise and all that being so important to comedy. But surprise relies on normalcy; you need to expect something so to discover something unexpected. How you believe an exchange (or scene) will end is often proved wrong in some way. And this belief, this expectation as well as its subversion, is provided by us the improvisers. We must play it straight, deliver the proper lines and proper emotion and do the real theater for it to work.

We are periodically bending how the scene will end, so that means periodically we also allow it to run its course as expected. This makes us a lot more trustworthy, so it’s easier to mislead the audience later. Aint we stinkers. But we also want to be trustworthy, to deliver as expected, so they audience can engage not just so they can be tricked, but engaged so they are engaged. We might be changing how the scene might end, we might even temporarily leave them have no idea how it will end, but in a good scene they are always confident it will indeed end. At the end of Wacky races, somebody will reach the finish line. The race is over.

But Crazy Town is never over. You are stuck in Crazytown. In Wacky Races, you are always moving towards a goal. In Crazytown, you can’t move anywhere. Even if you tried, you’d just find more crazy. Wacky races has the open air, room to breath. The worse thing about Crazytown is not, for instance, the gorilla swinging a chainsaw, it the fact your stuck in cage with a chainsaw gorilla. It’s the claustrophobia, the feeling you will never escape Crazy Town. I’m not talking about the characters any more either; the people in the audience are literally stuck in a room with weird and often hugely offensive noise makers and they don’t know why. I you don’t know why something is happening, its hard to predict what will happen next.

Rule Six: They‘re in this together

Let’s look at the Crazy Town picture again.

It’s a great deception of Crazy Town, because any of those elements on their own would be easy enough to swallow. A snake birthday party? Fine! The devil? Sure. In a world where snakes wear hats, we could have birds wearing hats too sure. In a word where snakes blow party blowers, mice can blow horns. In a world with sad rain clouds, of course they’d be sad if people were happy under their umbrellas.

The problem is this. These are several contexts, several scenes, but here they’re different words collided. Actually, not collided, because at least their impact isn’t felt. Nobody is talking to each other at the party. The senator dog ignores the cloud. the mice ignore the senator. Of course everyone ignores the headless man, everyone is ignoring everything. And with nobody bouncing off each other, informing each other, nothing is happening, and if it did it would be like nothing happened. No scene. No comedy. No good.

Leaving Crazy Town: Three Bucks, Two Bags, One Me

OK, the million dollar question; now how do you escape Crazy Town?

It’s not easy, I’ll be honest. Crazy Town scenes oft start on the wrong foot, and gradually get far worse. They are rotten from the inside, and frankly there are few scenes better solved simply by wiping. The audience will sigh in relief that The Scene Without an End has an end.

But you didn’t read this far to simply edit. You want to be the hero! You want to be the starting pistol (the living loaded starter pistol) to a better scene! Let’s see what we can do

Before we begin our prognosis, lets look at the diagnosis. To my eyes, the sickness in Crazy Town scenes comes down to two related problems

- Nobody is looking to react. All robbers, no police. All bent, no straight

- Even if they were looking to react, when everyone is absurd (and absurd in their own way) it’s hard to choose who to deal with / react to first. As Ian Robert’s says, it’s like painting a blue horse against a blue background; it’s hard to see, and get a bead on things.

So, you’re in Crazy Town. What do you do?

Hot Tip One: Its never too late for you, and your character, to be a straight man

It is never too late for the penny to drop, the politeness to fall away, the train to stop in its tracks. This is especially true in a crazy town scene, if one person just finds one thing crazy, at least now we have some chance of finding our bearings. There is one character we recognize as real, and there is at least one aspect they acknowledge as unreal. Progress.

It need not matter how deep you are in crazy yourself, or how high the pile of odd details has become; if your are the devil, it’s even funnier you too have a problem with double dippers.

In case it’s unclear from my example, the goal here isn’t to make a molehill out of a mundane activity (like double dipping), although that’s not a bad move. More likely is you’ll have a smorgasbord of weird things to find weird, so you shouldn’t need to fish around for too long, or heaven forbid introduce another fresh weird detail. In an ideal world, you are tying as many loose threads together as you can to make it all seem planned and genius.

Hot (related) Tip Two: It’s never too late for a character to start caring.

This is perhaps a wider tip, and therefore it might be less actionable than the straight man change. A straight man reveal can be a shot of adrenaline to the collapsed corpse of scene, a direct intervention used to jump start the actual scene. Do not be discouraged though; Caring is just as useful, it’s just less adrenaline shot more bowl of chicken soup. On the plus side, it is a tip that can be picked up by any character at any time, indeed it can be picked up by all the characters individually. What’s more, the character becomes stronger and more ‘them’.

Simply have your character care about a somebody, or something.

That somebody might be themselves, but caring and showing you care is shockingly rare in crazy town scenes. Every time a character makes a move, this should affect your character like ripples in the water. Your whole world, however small, has changed.

Actions without reactions might as well not have happened, and if nothing happened…nothing happened. Despise all the noise and the crazy voices and angry offers, nothing happened. Characters just float about doing whatever for whatever reason is the difference between a wet sack of car parts and a working engine.

Showing you care is just as important as caring. Make sure your using your face to react, asking questions, anything. You can simply say the words ‘I love’ or ‘I hate’ or even ‘I’m don’t care about’ if you want to push against my rules, if there’s a reason you don’t care, if you really care about how you don’t care.

Moving Out

In both cases, you are trying to get the scene moving. As mentioned, the fastest way to do this is just cut bait and edit away. We’ll call this the midnight teenage runaway method of moving out of crazy town. But the two methods we focused on (going straight, and caring) are different. Getting a scene going might sound like your moving on, but your actually dwelling on the details so the audience see’s their value. You are getting something started by finished what has been started.

In moving out terms, this would be like wrapping all your precious belongings and putting them in labelled boxes. We see what offers were precious to you, and which you’re leaving behind. We see what box the different items belong to. Childhood memories, perhaps?

Pitfalls

I mean, as soon as your in a crazy town scene something went wrong, so embrace the unfamiliar and try something. There’s nothing to break here.

Crazy Town scenes often feel like your waking in molasses, whilst breathing molasses.

Where your job gets harder is if your fellow team mates don’t pick up the breadcrumbs, and don’t react back. This is when you might want to turn up your reactions: increase the clarity, and perhaps the volume. Become more paranoid: every reaction means something deeper.

Because there’s always a reaction. Whatever you can see: a nod, a sigh, a blink too fast, something to grab onto and run to goal. If there is any reaction at all, call them on it, highlight it. ‘Oh, you seem hesitant’ or ‘ah, your thinking about it aren’t you’ or ‘don’t give me that look, poo makes a great present!’. Note that these reactions are super minor, and your making them bigger. You can even just make up their reaction HOWEVER this is harder because a) its touch teaching scene in that partner has to shut up as you show them exactly how its done, and b) they might, and often do,assume your character is lying ‘I don’t feel that! I wasn’t clutching my bag’ and now its just a wizard’s duel: a scene about two people arguing over truth in a game of make em ups.