Lesson Delta: GAMEPLAY

Actually Doing the Damn Thing

Introduction

Hello Everyone

Congratulations on making it this far: it’s been a slog

We’ve thrown away a lot of very basic, quite nice guidelines, and replaced them with a load of toss about scene types and position play and capital G Game and bullshit. It might be tempting to think ‘look, I dunno if all this improv stuff is for me, it’s way more maths than I expected, I’m just a dumb dummy who nobody likes’ or ‘screw these guys, this is bogus, they don’t know anything’. These thoughts are natural. The latter thought is actually true, I’m glad I didn’t have to admit it, Catherine and I are running a scam. But the former thought is not true. Well, ok maybe improv isn’t for you, but I hope that’s not true, and it may be mathy-er I don’t know your expectations. But it’s not as hard as we make it seem, and hopefully by the end of today you agree. This document hopefully addresses some of your questions, confusions and concerns. Ideally by the end you will have enough of a handle to put these theories and mind games into real to-the-paint practice.

And who will be asking these questions? Why it’s Biscuits, the helpful improv dinosaur.

Hello Biscuits! Why questions do you have for me?

I feel this is all a bit much

Oh no, poor Biscuits. Well, you know, keep in mind

1. The first three lessons of this course are probably the biggest, headiest, most dogmatic lessons of the lot. The rest is a lot more patting on the back and tips you can try to see if they stick. It’s nicer.

2. These lessons will also be mentioned over and over again, alongside the pats and tips, so you are not expected to Chad Carter just yet.

3. You can do this: you are an improv warrior, an advanced student. You had your chance to walk away, and you blew it: you’re one of us now

What was the first lessons about?

Oh, ok wow we’re going right back. Ok sure, let’s recap some more

Lesson 1: You are enough, I want to hear you opinions and reactions in a scene, you are an asshole. We will be re-exploring this is a big way today. That’s lesson 1, done.

Lesson 2: The four scene types, which aren’t the only definitions of scene types out there, are Shared Perspective ( fruit in a bowl, two folks fucking, we are weird together), its cousin Shared Perspective (alternate reality, the world is world together), Straight/Bent (sane man crazy man, two folks fighting, you are weird and I am not) and its cousin Realistic (normal, nobody’s weird expect ok maybe you and I but mostly you a little). That’s Lesson 2, done

What about Lesson 3

Lesson 3 was Game of the Scene. Did you have a question about that?

What is The Game of the Scene….exactly.

Haha, sure.

A game is a pattern wherein a stimulus triggers an emotional response (whether the stimulus is unusual and the response is normal or the stimulus is normal and the response is unusual makes no difference for sake of this definition). Further exploration of stimuli is done with the goal of eliciting a more heightened emotional response.

Is that clear? Of course not

Game is the reaction to the unusual thing that deviated from an established reality, and is repeatable in a justifiable and enjoyable way.

Clearer? Not bad, but we’ll try again.

The game is the one big funny thing in the scene. Funny as in both humorous, and unusual. Funny tasting. The game is what the scene is about.

That is The Game. That is all it is.

So why am I still confused?

A small tripping point I find is in semantics. The Game is different than Game. The Game is the thing the scene’s about, Game is how you play the scene. When you play The Game, you’re playing Game. The Game is the tune, Game is the notes. The Game is basketball, Game is us playing basketball. Why they gave such closely intertwined yet very separate things almost identical names is a mystery. A very annoying mystery.

Alright, so what is Game then.

Game made dead simple: What is funny? Keep it funny.

To me The Game is absolutely everywhere, everywhere, in every successful scene by every kind of person. No exceptions. Game is a good way of showcasing The Game, but if it might not be for you.

It seems very clinical, and thinky, and less spontaneous.

I hear you, but no I don’t think so. It’s only as clinical ie boring in how you react and how you explore. You can still put your flavour on it, in fact it won’t really work if you don’t. The Game should be obvious (the funnier the easier usually), so you shouldn’t outside of class have to think THAT much. Finally, just so we’re clear, comedy is never spontaneous: whether it is confirming or going against a stimulus, the stimulus is always there.

Game like any game refers to both what we’re playing (the game), and how we play it (game). Recognising what is funny is key, implementing how to make it funny is key. BOTH skills you’re ALWAYS doing and how you play is obviously an organic ongoing thing. Like a basketball game. I will use the basketball analogy too much.

Can you give an example of a game (The Game)

I sure can. Again, it’s just describing what is funny. It will be, in my opinion, a combination of the specific (he has a dead parrot) and the general (he is angry) to meet in the middle (a shop keeper is shifty about a returns policy, poorly/successfully up to you). This is both specific and universal. Every game is unique, and every game has been done before.

You will need at least one source (person or nay) of the unusual, and at least one source of reason (pretty much person).

This is because while The Game is often stated without the reaction, the reaction is vital to Game.

To that end, many games could be described by DESPITE. ‘A guy eats his sandwich loudly DESPITE a warrior trying to hear a trap about to be sprung’

Well that cover’s a straight/bent scene, what about game in a Shared Perspective or Alternate Reality scene. Here are some good phrases for describing that game, via UCB teacher Will Hines.

WHAT IF: Title the game with a “What If” — “what if the top clique at a high school were scientists?”.

INSTEAD OF: Say “instead of” to clarify: “So, a version of the show Cops but instead of domestic violence and drug deals they bust people who play sex games.”

AS IF: “A guy who tries to wow his date with a fried egg as if it were caviar / champagne.”

Actually to be fair I’d personally probably play that last example as straight/bent, but it’s as you wish. How you play Game (like how you play basketball) is all about the player.

Ok, we recognize The Game. Now how to do we play Game.

First of all, definitely make sure you have that reaction to the unusual thing locked.

Good news, it doesn’t always have to be a straight reaction. They can think the unusual thing is a great idea, as long as they thing is still seen as The Thing and not just another thing in a long list of normal things.

Once there’s a reaction, it’s game, so who would give a good reaction? What would be a good foil for the characters? An opposite? A rival? A lover? A jilted lover, a potential lover, a big fan, a mother, a spurned mother, an opposite mother, a rival mother? The world is your oyster. They could be oysters!

I promise, I have The Game. Unusual thing plus reaction. What comes after that three second exchange?

It is now time to Heighten and Explore. Check out this diagram

Heightening and Exploring work in tandem to keep your seen going. Like stair steps, each direction is important; you must do both to keep the scenes going.

This is nonsense

No it’s….I’ll try to break it down.

Heightening

Heightening is fairly easy to grasp: whatever was unusual, deviant, funny, give us more of it. If a character is greedy, make him greedier. If the fart is funny, fart harder. If a statue is broken by a security guard, it will break more. You might increase the intensity of the unusual thing, or the frequency. Heighten can also include increasing the reaction of the audience’s surrogate (the polarity). Heighten can also mean to increase the severity of the unusual thing, by ‘raising the stakes’ or making the scenario even less conducive for the unusual thing to go by abated. The character is greedy….at a benefit for the starving. You fart….in front of the president. Mother’s in law, desert islands, life or death, the list goes on.

So heightening is increasing

To an extent, although there’s a difference between heightening and increasing. Increasing just adds more stuff; heightening is specific to your character and pov and playing more of that. The world doesn’t just get bigger/wilder/deeper, but the character’s (straight and bent) reactions do too. More enthusiastic, or more annoyed.

I’m with you. I think I get Heightening. I’m a little shakier on Exploring.

Exploring

Exploring is a tricker concept I feel, because its function and application is looser.

Exploring stops you just heightening blindly, like a robot. Exploring at its most basic function gives you time between heightening the game so it feel more organic and more of a surprise. Treading water you could ungenerously call it. It allows you to rest The Game

Wait what! You just said The Game is what we should be doing all the time, ringing that bell is what the whole scene is about?

It is, but too much can be a good thing

Then….what, we don’t we just say a bunch of unrelated funny lines, like I was doing before!

Calm down, calm down, have faith. That’s simply much harder to do, and much less funny. Is that what you want?

Obviously not

Yes, Resting The Game is a real thing in Game. The Game is the hook of your pop song, and it’s great, but you gotta have at least a little down time so you don’t immediately get sick of it, and it’s pure noise. There She Goes, by The La’s, is a crazy simple pop song. It’s like four lines repeated over and over. But it still has that cool drum bit that makes you nostalgic for the hook you heard mere seconds ago. Plus a nice bridge.

Exploring at its most basic can be that bridge. You could see it as simply playing the base reality some more, like you did at the start of the scene, to resell the normalcy of the world that you can better bounce against with the unusual thing.

Exploring allows you to in new and interesting ways execute the setting or scenario some more, following the USUAL thing. So, in a mechanic scene, have a new car come in, check the tyres, go over the bill, wash your hands on an oily rag etc. This is easy, as this base reality should be definition be obvious and familiar to you and the audience, so just play the reality. No invention needed, just reflection, and will give you lovely breathing room to think of your next move.

But exploring doesn’t stop there.

The next level of exploring gives you fodder to feed the heighten, as well as clues in the environment where that heighten is going to be.

Exploring can be looking for things in the base reality to put through the unusual-thing-o-matic. ‘hey man you are meant to be helping me clean, instead you ate all my sandwiches. God damn it, and you made the mess worse with crumbs! Here’s a broom….oih, you ate the broom, dude!’. I know in examples it sounds dumb, but it’s true, and it’s easy. By being true to the base reality, the audience will accept it, and allow you some time to add a twist with new specifics. It is feeding the scene, and extra special awesome bonus it also feels RIGHT, not simply an obvious feedline. You don’t have to, but I call these details firewood.

Exploring also allows you to explore the consequences of your character’s behaviour. The consequences of this unusual thing being a part of the world. Ask yourself ‘If this is true, what else is true?;

I repeat that again, ask ‘if this is true what else is true’. This phrase is a cornerstone of Game. In stark terms, it lets you have several punchlines off a single premise, which is the goal surely. ‘If this is true what else is true’ will not only produce laughs on its own, but increase the laughter you get from heightening alone, while making your scene feel richer and deeper and more realistic for an audience. That’s because it provides a logic, rationale or philosophy behind the absurdity. If this is true, WHY is it true. Justifying the behaviour.

Whoah whoah, Logic? Justification? Doesn’t that just explain away the funny?

Trust me, justifying is a crucial part of exploring. It gives the audience a buy in. If you do it right, it won’t explain away the funny: the explanation will invite more funny to come forward.

Funny patterns done for funny reasons are great. A man struggling to lift a metal umbrella is kinda funny. Finding out it’s because he wanted the hardiest umbrella possible, for all kinds of bad weather, is funnier (or at least we have more to talk about). And it’s funny for a different reason than say if the man had a metal umbrella because it’s gold leaf and he will only have the finest most expensive items available (practicality be damned). Just because we present a logic, doesn’t mean it’s logical (metal umbrellas are hardy but impractical). Just because it’s a philosophy, doesn’t mean it’s a good one (expensive doesn’t actually equal the best). I should clarify something I said before ‘funny patterns done for funny reasons’ doesn’t mean the reasons are unrelatable. On the contrary, comedy thrives on the deep seated universality of these reasons. Think of you favourite comedic scenes: I bet you the series of unfortunate events that produced that comedy were motivated by big motivators such as love, lust, vanity, envy, revenge (Itchy and Scratchy), and greed (Wile E Coyote, the original Itchy and Scratchy…no wait that’s Tom and Jerry). Every fairy floss light hearted comedy has a hard serious centre. Comedy is drama but subtler.

Aren’t crazy characters just … crazy? They’re illogical, whackadoo, that’s why we love them!

That’s a hard no. I don’t want to dwell too much on why this is a falsehood (I mean, I do, I’ve done it before), but frankly no: crazy isn’t that funny, in fact it’s sometimes sad and usually frustrating to watch. An audience will tend to sit there in angry silence, trying to work out with the heck is happening. You might catch a few stray short sharp laughs out of surprise or simply release, but you don’t want to rely on them. The characters we love, if you want to put it that way, are relatable.

But one of the best things about improv (particularly) is how anything could happen, and how we end up in these crazy scenes with talking toilets and crocodiles with human penises. I’ve seen you do those scenes they’re very funny, you are very funny, you should have some sort of government grant for being funny.

Well first of all thank you for your praise, and please write to your local representative. But I do think you answered your own question, we END UP in those scenes. As Neil Casey says, we can go to crazy town but we have to take the local. That means, the audiences has to see each stop how we got there. There’s a scene in Liar Liar where Jim Carry emerges from behind a desk covered in ink saying ‘the god damn pen is blue’. I love it. Would it be funny on it own? Maybe a little: Unusual thing on face, unusual thing to say, even a somewhat unusual thing to emerge from behind (never underestimate the power of peek-a-boo in comedy and horror). But believe me it’s far funnier in the context of the movie, with the large amounts of steps that it took to reach that point (involving birthday wishes and frustration after frustration and a Hands of Orlac slapstick fight scene). Game is not about simply creating problems, or solving problems, but creating problems by solving problems. She swallowed a spider to catch the fly. He launched the rocket to catch the roadrunner. He faked muscles to impress the girl. She climbed the filmiest branch over the angry dog pound to retrieve the errant lottery ticket. He draw on his face to succumb to his inability to lie. Adam McKay, improviser and writer of most of Will Farrell’s work, sums up game of the scene as this “I know it’s weird that I blank, but it’s because of blank”.

… Will Ferrell plays some pretty crazy characters though

Look, fine, use your terms if you like. But I mean everyone does everything for a reason, even the crazy have their reasons: we call them manifestos (thank you Billy Merritt).

Great, I think I’m on board now. Justifying isn’t stopping the comedy, it’s (like exploring) creating more opportunities for the comedy to exist, in this case inventing backstory and reasons for your character to be who they are, and for behaving as they do.

I think that’s a pretty solid understanding. I will say, don’t feel like you need to ‘invent’ so much. You can just discover. That’s why it’s called exploring.

You’re killing me dude, I didn’t ask you about any of this

Yeah, you’re right. A lot of this ‘discover not invent’ improv philosophy might be better served for another day.

I will talk a little about it, only because I do think it’s quite a big part of the ‘explore’ side of heighten and explore. Don’t be afraid to simply explore what you already know in a scene, rather than stressing trying to invent more things, come up with additional clever plot points, and more jokes. A key reason The Game stays the same, is so we have something to work with. Honestly, everything you need in a scene was probably in the first couple of lines. If you’re in doubt, go back to them. ‘Whatever man, we’re meant to be driving this ship’ or ‘oh god, all I asked was good morning’ or if you’re the bent ‘come on, lots of corn to husk’ or ‘happy birthday anyway’. A lot of scenes end with just us acknowledging the beginning again it’s circular, it neat, it feels good.

Oh oh, actually I’m glad you mentioned the end. I’ve seen you play, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of ends exactly; you more often than not cutting to another scene that relates this one.

Excellent observation. Because yes heightening and exploring for sure goes beyond the single scene. When I, and now you, cut to another location in scene I am either actively heightening (raising the stakes is very big here), or actively exploring (if this is true, what else is true of the world). To a certain extent, you might also change locations to play a new game that organically sprouted.

Wait wait, you can change games? Surely the whole point was you stick to your guns?

You do, until that particular game has run its course. After that, you follow the new game as it arises, or you simply edit the scene.

Ok, I…

I will get to it, promise.

Fine. Please do. Because I’m beginning to think you’re full of shit.

A problem I felt learning about Heighten and Exploring was semantics

Semantics again? Jesus, this is going to be long isn’t it…

A little. You can skip it if you like.

I’m not sure heighten is the right word. I don’t have one better, but to me it seems…over eager? Mechanical? It’s sometimes called Raising the stakes, which is good advice but definitely the wrong word because it boxes you into a particular type of heightening. You can heighten the behaviour not just the stakes, or your reaction to the behaviour. You are boiling the water, however you apply that heat is the right way. A big reaction demands a big reaction, and if you don’t get it that’s also a big reaction because it’s a stark contrast ie big. Catherine talked about the idiosyncratic choices available in Game very well already so I won’t dwell, but considering all your doing is doing the funny thing Heighten as a word seems so one note. I dunno.

Explore is definitely the right word. You should be curious, you should be playful, and you should not be entirely sure what you’ll find. The questions you are asking in your head are the questions you should be saying out loud. If you’re confused, the audience is, so address that confusion. If you find something funny, follow it, the audience probably agrees. Exploring is where your uniqueness superpowers really come out, where you show why it is you we are watching in a scene. Exploring directly leads to heightening. And heightening to exploring. Remember the stairs? It’s maybe closer to a mountain side: sometimes the incline is stark and obvious, sometimes not. Heighten and Explore are not synonymous, but they do work in tandem and they can be similar, especially when you try to study them.

Example time!

Butler: No you can not ride your dirt bike in here….this is the palace and you are the queen.

Now is this heighten? Heck yeah, stakes raised twice over: there’s the status of location (a very fragile location I might add as it’s a combination of museum and priceless artefact store), as well as the status of person (it would be very improper for a queen to be on a dirt bike).

However, it’s also an exploration: the move has added history and context to the tale, it has established more of a relationship, it has (and in my opinion this is crucial) added an entirely different room in the house of The Game to explore.

It begs so many questions from me, it provides so many more paths, it makes that little bit of your curious brain just fizz. There are so many scenes we can do now, all funny. If I am playing a Queen on a dirtbike, do I focus on the old nature of the queen, and how injured she could get on a dirt bike? Do I focus on the regal nature of the queen; what does this mean to our sovereignty if the queen dies, especially in such a manner? Do I focus on the powerful nature of the queen; she is the queen, she makes the rules, she is making a rule that the queen can ride a fucking dirtbike? How exactly do you stop a queen on a dirtbike anyway? Do I keep being polite, do I beg, do I let it go, do I hit her with a block of wood?

There is a perception that game limits your comedy. I understand this view: it’s literally limiting your comedy. But I still strongly disagree. Game to me makes you got to so many wild and wonderful places I wouldn’t be able to reach without it, and this Exploration to me is key. If I spend five minutes in Paris, I see the Eiffel tower, then I have to move on to Germany. I stay in Paris, fuck me the things I could find. I try the cuisine, I learn to cook the cuisine, I become a chef, the best chef in the land, I become arrogant and refuse to cook for customers only myself, I lose all my money, I sleep under the tower, I meet a beautiful French tramp, we make love, we become lover-robbers, stealing from the tourists as riff raff, our love becomes so strong our bodies start fusing together, we become a tree, our tree bears fruit, that fruit becomes the local cuisine. All that because I didn’t leave Paris at the tower. And by the way: that was massively plotty, any of those beats would be more than enough for a scene if I delved even deeper, exploring even more. Its like fractals. Turtles all the way down.

I mentioned plot just now, because I like plot. It gets a real bad rap though, and confusingly you will hear the note ‘follow the game, not the plot’. What this means is keep exploring this unusual thing, instead of just moving the story along to something else. You hear this from very good teachers, better teachers that me. And I agree with them, I just feel….and this is a little controversial….it may be a misunderstanding of plot. Plot can be a very useful tool of game. Look, it’s a lesson for a few weeks time..

Good. Stop.

BUT since we have a good example here I will do a quite demonstration. Plot to me is all about consequences: this happened, therefore as a result this happened. If this, then what. Classic game. It is especially good for finding a second beat, where you want to look outside the scene, and to my taste outside these four walls.

Alright, you have your queen on a dirt bike. Who can enter, what outside force can affect or ideally be affected by this unusual thing: a rival queen (or probably Tsar or something to add a little contrast for roughage) challenged the queen to a dirtbike contest. Is this a different unusual thing? Yes. But is the unusual thing alone what makes The Game?

No

No it’s not. So we keep the same reaction: if the Butler was worried about mess, he sure is now. If the Butler was worried about status, oh boy we could lose it all. If the Queen was old, the Tsar is older, or rougher threatening the Queen’s body, or more accident prone, or what have you.

Finally, we get to my question: You are saying, on the record, that The Game can change?

Well first of all, I encourage to try and have a clear concise Game of the Scene, and to stick to it, especially as your learning. Do not change your Game out of lack of talent, concentration, panic fire, or simply fear of being not enough.

Yeah yeah, but you can change your game?

There are several thoughts, but the short answer is yes. To start with, however long I make these notes, improv is still making a scene up as you go along. It’s the skin of your teeth and the seat of your pants, and when it’s time to speak you gotta speak. As such mistakes are going to be made, and compounded upon, and fun little oddities in the scene will sprout. This is normal. This is part of the fun. Game to me is AS MUCH IF NOT MORE SO capitalising on these odd choices and twists in the scene. Discovery not invention, because like it or not (I like it) unusual things are going to arise. The Game of the Scene initially very well could have come out of odd moves at the top of the scene.

Example time!

Your partner comes out, clearly doing the inauguration speech of Abraham Lincoln, and you mistake if for the speech Blade gives about killing vampires. Well good for you, you’re now doing a scene where Abraham Lincoln is an action movie vampire hunter (copyright Manfred Yon 2016, any films past or future with this exact premise owe me money). And what happens when later in the scene a player is pimped as Mary Todd Lincoln and puts on a Marilyn Monroe characterisation (which is clever) but the other player doesn’t see the connection so calls her out AS Marilyn Monroe, well now I guess Abraham Lincoln has a time machine for fighting evil creatures so he went to the 1960’s to kill the werewolf king with a silver bullet because the werewolf king was totally JFK and it was Abraham Lincoln the whole time and he saved Marilyn Monroe from the clutches of that evil werewolf king and brought her back to his time we she can be safe from werewolf retribution.

Welcome to improv.

So yes, you can and will change The Game sometimes.

To me though, this is where the Game side of it comes in, because it will let you do that. Exploration, asking questions, if this is true what else is true, lets The Game not simply change, but evolve.

Ok, that’s reassuring. Well….can you change the game yourself, cart blanc, because you want to?

Again, all provisos of learning to stick to your guns etc etc, yes you can. I would advise restraint, because like it will change anyway so instigating change despite your best intentions runs the risk of over-salting the soup. But if you want to do it, and I do it, you have to make sure you have all the main parts ie reaction and base reality etc, that stays intact and if it wobbles you address it and fix it. You can fix it for real ie make it okay in the scene (eg in the dirtbike queen scene ‘luckily all these palace vases are actually bouncy plastic’) or you can hang a lantern (‘I’m just going to say goodbye to these vases now’ or simply ‘oh fuck, but the vases!’). Changing the game, or the focus of the scene, usually involves a change in location, and in my opinion a little breathing room is called for so the audience can mentally transition from the one scene to another (I call them separate scenes, because they have separate games). In a long form format, with multiple scenes, this might be called for anyway. In a single scene, a lot less often. A lot less.

But like I say, crazy details come up that take focus/your interest. A good rule of thumb, according to Alex Fernie, is to follow this line of inquiry IF the previous game feels well enough explored. It doesn’t need to be exhausted, although if it is it’s a perfect time to leave, maybe it’s got enough legs to be REINTRODUCED later. But generally, try not to chase the coin that rolled out from the sack of treasure, cause you’ll lose the treasure.

So there’s really not hard and fast rules when to change the game, it’s a personal thing.

It sure is. That said though, there are exceptions. Some formats for instance demand you chase the coin. The Monoscene is a single location, single timeline, no cut aways one act play basically. By its nature, you will probably follow several tracts within the same scene without my handy change in location. Even more pronounced is the Pretty Flower, a monoscene with tag outs that will explore a game to its completion within a single tag run. On the other hand, there are formats where a new game is a no-no, such as a Harold. The Harold is often used as a training exercise because it’s so strict.

Did you say we can play multiple games in the same scene?

Oh boy you just want to see the world burn don’t you. Yes, there is the hazy, but potentially very very rewarding, playing multiple games in a single scene. Following the treasure idea, you might be on a pirate ship that keeps getting hit by a wave, making you all fall over (game), while discussing whether mermaids exist (game), or something. There is probably a third game where this sort of discussing should wait for a better moment, that umbrellas both games making it the one true game (which would mean both the minor games would evolve, so it’s not just waves but a giant squid, and it’s not just a cryptozoology talk but perhaps one of the more finiky subject of semantics), which I’m not sure proves or disproves my point that multiple games both ENHANCES the scene/show, makes it more layered and interesting while at the same time (although it has its pratfalls of complexity and group mind) allows you more time to add steps to the game exploration, because you can let it rest. Ok ok, simplify. Let’s say it’s a game of…a pirate is trying to convince his girlfriend that being on the sea, pirating, with him is romantic and great. So we see how she gets sea sick, or how the food sucks, or the people on ship smell. Now let’s say we have a parrot who says swear words on the chiming of a cuckoo clock, that’s also there on board. Now, see, even that, my instinct is to make it another thing she doesn’t like, or that the clock chimes just in time to punctuate the conversation with ‘that bastard’ or ‘slut’ or something. Alright, here we go again, some premise, some ship, one of the things she doesn’t like is a cook who has hands like a crab. Well then every so often he can be unable to do something with his crab hands. Now this I suppose again plays into the broad game of ‘she hates it here’, but really it is its own separate little thing. But could you have a scene where the couple are having a deep conversation, and in the background he is trying to peel a banana with his claws. Maybe that is the rule, having a unity of space or theme is allowed. Grr, this proves nothing. Maybe it goes back to the original Alex Fernie point: you can get distracted, go all over the board, but wrap up or TIE IN your MAIN game. Be on the lookout for what is the MAIN game and, true to classic rule, it’s probably the FIRST thing we were introduced to.

Forget I said anything

No no I want to crack this now. I am going to say for sure you can have games WITHIN games i.e a family outing with a coach-dad, might have yelling or inspiring monologues, it might have a ‘formation’ every few minutes, it might have a son going to complain and getting shut down more and more. These games support The Game of the Scene, but they are still games in their own right, little patterns, with recurring reactions. Additional little games also, like exploring allow you to rest the main game, so you don’t kill it with intensity. You can have multiple games, as mentioned, or exploring ‘if this is true’ in the same room, not just heightening. Or when you return to the base reality, to as mentioned ‘do the thing’ so you can find more ways to showcase The Game, you could do it in a recurring way so it creates a fun little pattern.

Example time

Deli-Owner: And that’s how I would murder my pets. Buuuuuut enough of that, did you say you wanted extra egg on your sandwich? Mayo? You know that cholesterol will kill ya hahaha. Just like I would kill my dog, slowly, painfully. Buuuuut enough of that, you want beetroot on this thing? Looks like blood. Dog blood. Delicious. Buuuuuut enough of that’ etc forever and ever until the audience leaves.

Sometimes, and I know it feels counter intuitive, but a little extra (particular character) unrelated something makes a game soar. A character has a limp, or your straight man has a squeaky voice.

Think of game as the main course. You can, and should, step away for spices and relishes and fun little side dishes, but you should always come back to your main thing. Without the sides and spices, the main would be very bald, predictable, you may get a little sick of it. But you can’t just whack any old thing with any old thing, flavours must compliment, go together.

In this sketch from the Tonight Show of all places, we have to me perfect game. It has a base reality, a familiar thing to keep returning to. It has clear heightening, more and more things are horse themed. It has clear exploring, we ask why the horses are important, if this is true what else is true. It has personal justification. And it has a separate second game (the chorus isn’t coming, and Jeff Lyne wants to sing). The second game is minor, never overshadowing the main Game of the Scene. But right at the end, the two games merge, supporting each other, becoming something more. Beautiful.

Leave a tidy house before you go to work, because you don’t want to be thinking about the iron they left on (in this case, the audience still thinking about the last scene or The Game when you’re in the next)

Or, to push the metaphor, only leave your door unlocked if you’ll be gone a second but you’re heading back in. Because that to me is what a certain kind of button is, it’s an ending that’s great (often really great), but it locks the house behind you, so if you want to get back in, you gotta unlock the lock. This might take a whole scene, or be a quick line. It’s one of the hardest things about sequels in general.

Any more questions?

Despite myself, yes, I do have a few more

Is it better to have a premise, or open organically. What is the best opener, basically.

Completely up to you, and circumstance. If you have a premise, go for it. If you don’t, go for it. If your format has a big opening, I would try to use premise just so there’s a clear connection between it and the format. It took time and energy, make it worthwhile. As a general rule, and this is pure statistics in my improv life, premise gets the funny quicker, but organic makes an audience laugh more when it arrives. After a minute or so, they both look the same anyway. I mean identical. Your “premise” of the scene doesn’t have to be funny, in fact it doesn’t even matter soon. It’s the champagne on the boat, it just launches the thing.

Save yourself the work; You don’t have to do as much as you think. There’s no perfect opener. There is a perfect reaction, but only because it was completely in that moment.

Can anything be The Game

Sure, anything you find funny. Okay, anything the audience finds funny. Obviously there are things I find funnier than other things, that’s just the way it goes. If you even want to make me laugh, arbitrarily, at any point in any scene, make one character poop their pants. I can’t help it, it always works for me: if they were already low status they just got lower, if their high status they just lost it all. Genius. I also like arrogant idiots who mean no harm, and the movie Grease.

Then there are things that come up quite a bit, especially with new improvisers, I just don’t latch onto (and frankly neither do a lot of audiences).

1. A ‘crazy world’ alone is not much of a game. For instance, two kids finding a dragon egg and hatching the dragon egg and then flying on the dragon is a children’s story, it aint funny, stop it. That might be obvious, but it’s not always. Maybe you’re playing in a world where everything is lego, so there’s lego pants, lego sandwiches, basically the lego movie. It feels funny, it is funny to an extent (it’s a fun place to be), but alone no it’s not game. The Lego Movie has a plot, as does its trailer, your scene does not. As a backdrop I love it, but not alone. Audiences get habitualised to weird worlds pretty quickly, before they need some good old fashioned human drama.

2. Being a racist (or sexist or whatever) isn’t much of a game. Yes it’s unusual, inappropriate, illogical, the reactions there, but…it just doesn’t really work, trust me, I am still learning this lesson. This isn’t a blanket ban on playing a racist or offending people, although do keep in mind you easily might, it just usually goes ok at best. You need something more. KKK trying new outfit choices might work, Hitler being sad watching Golden Girls can be funny, even someone acting racist about something that we aren’t usually etc to people with non-matching eyebrows can be funny although personally I think it’s a little clapped out. Weirdly being judgemental to say the mentally challenged or the elderly seems more offensive and ‘done’ and I’m not sure why. Wide berth if you want my advice, even if you see me doing it.

3. I personally don’t much like ‘wacky accent/voice/wording’ dude character, but this might be my own taste. But I mean how do you react to that? ‘hey, that’s not what my voice sounds like’, just let the weirdo be, who cares.

4. Gay Person. This one I find weird that it comes up at all, and not because it’s not PC. You can play a character who is gay sure, but a character who is gay as their defining trait. Often they are inappropriately sexual, which yes is a game, but often not they’re….just gay. That’s not unusual. I don’t just mean we need to accept our gay community and see it as normal, but…it’s certainly not unusual enough to warrent a scene (a lot of scenes it seems)? Sometimes obviously it’’s coming from a place of slight or overt homophobia ie they get treated like someone was say openly paedophilic or necrophilic or bowl-of-unwashed-corn-philic (we could argue about accepting all sexualities but for now in our society at large these are considered double take reaction worthy when admitting in a shitty comedy scene). Sometimes it’s coming from stereotypes closer to my wacky voice character game. Sometimes they will take offense at non-offense stuff, claiming its homophobic or prejudicial (this is a game, not one I like much but ok). Sure, there is also plenty of ‘I am a manly dude, isn’t it novel that I’m paying a guy who says in a scene he’s gay, that’s pretty progressive really, it’ll be cool if I was gay right? Because I have something to say: I think dudes I might be gay No homo!’. But sometimes they’re just….gay. Like, they will be in a transaction scene, and just be talking about being gay, going in gay dates, wondering if certain celebrities like them are gay. Maybe I just don’t get it, I dunno.

5. People pretending to be animals. Or babies. Please guys, if you want to do that in a scene okay fine go nuts, but the scene is not about that alone please? Please don’t make me scratch behind your imaginary ears, and so help me if you cry in a scene 55 year old fake baby I will stomp you to the curb. Ahem

6. High School Musical. You’re not Grease, get outta here.

But yes all things said anything can be a Game.

Any final tips? Please, keep it short

If you miss the game, its ok to try to steer it back to what it was if you can. Especially if you sweep it.

If the scene isn’t working, try to simply tie it up, and sweep. Leave it behind, it’s ok, maybe someone can use it later, there’s a good chance there was something funny there.

Often the justification is the game, a little piece of dream logic that doesn’t necessarily make sense.

And finally, which is always my tip: Don’t explore at arm’s length: let your character care. Let yourself care. Give a shit. Get mad, get curious, follow your funny. It’s the single best weapon you have in that scene, follow your funny.

Further Reading

There is a good analogy for looking at philosophy through justification called ‘The Hand’ by Alex Berg. Seriously, it’s good, you’ll use it. I’d click it on. It has pictures.

My piece on labelling someone as ‘crazy’ in a scene. http://improvalchemy.tumblr.com/post/150082009094/like-crazy

Here is the surprisingly good sketch from The Tonight Show with guest Kevin Bacon.

I’ve skipped the dumb over-explaining beginning for your convenience.

Here is the song ‘There She Goes’ by The La’s. I’m pretty sure you already know it.

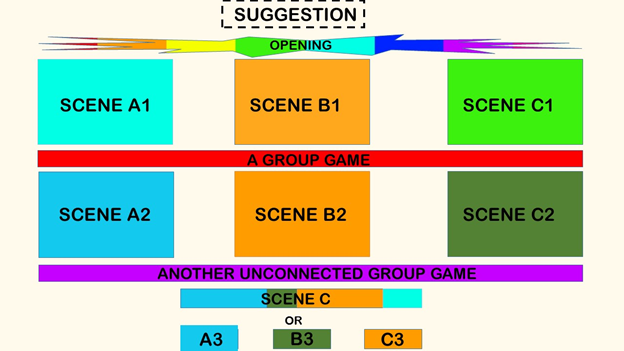

Activities: New Format : Harry

This week’s format was a Harry. It is a simplified version of the grandaddy format The Harold (Harry is a Harold in a hurry)

The Harold, to some long-form theatres, is huge. It is one of the oldest formats (the timeline gets fuzzy), most other formats are a version of The Harold, and it’s the official format of IO (Chicago, where The Harold was invented), UCB (NY and LA, where they have house Harold teams and house Harold minor teams) and Improv Conspiracy (Melbourne) amongst others. Many places teach it as an entire level, or more, on The Harold alone. So to give every thought on it would be folly, and I’m getting hungry, so here is a crash course.

While The Harold, being an old format, has many forms (it’s creator Del Close said ‘anything over 20 minutes is a Harold’ which is frankly silly), one has largely become the standard set structure.

This one.

It is sometimes called The Training Wheels Harold, which implies there’s a harder Harold you are working towards. That’s frightening. This one is complicated enough.

By comparison, this is a standard montage

While the Montage is a series of unrelated scenes (it doesn’t actually have to be, they can be related, and frequently are, it’s a very loose format), The Harold is not. Some scenes have to be related, some have to be unrelated, all in a particular order.

It is often used as a training format (training wheels I suppose) because it contains a lot of different scene types and skills you can then use in looser formats, like The Montage (Pack Theatre uses The Deconstruction for this effect).

Here is how it runs.

You take a suggestion, then perform an opening (a ritualized mini-format, there are several types, that explores a suggestion without doing scenes, ideally so all players are thinking along the same lines ie group mind).

From the opening, not the suggestion, three unrelated scenes (unrelated to each other, completely doggedly related to the opening) are performed, each with two characters (no more, I suppose no less).

Then a quick group game, also from the opening, is performed. The three more unrelated scenes BUT FOLLOWING ON FROM THE FIRST THREE SCENES, and always in the original order. The first scene in the first lot (beat) will directly relate to the first scene in the second beat. Therefore they are Scene A1 and Scene A2.

In our terms, the corresponding scenes will share a Game. They might feature identical characters (Time Dash), one of the same characters (World Dash), or none (Analogous).

This beat may still take some elements from the opening, but don’t have to.

This beat can have other characters enter and exit, or cut to other locations, or whatever, but always exploring the same game.

Then you have another group game, related to the opening but maybe or maybe not related to the first opening (usually unrelated).

Then you have a third beat, the shortest beat, where you explore the respective games one final time. No new characters now, but you have the OPTION of having the elements from any of the scenes in any of the beats (including characters) interact with each other (ideally complimenting each other’s games). You can even do this as one single scene.

It’s a madhouse usually.

And that’s The Harold.

As hopefully you can see via the colour choices on the diagram, your second beat scenes can take more inspiration from the rainbow opening (A2 leads on from A1, but is also a similar colour to a different part of the opening), or they can be simply a continuation of their first counterpart (B1 and B2, much like how the Banana’s in Pajamas are the same), or they can be unrelated to the opening but a more pronounced version of the game present in the first beat’s counterpart.

I think this last option is a good example of a larger point: our first beat can be flawed, it can perhaps find its game slowly, just make it better in the second. We do second beats so we can do the perfect version of our first beat. In the best case, it allows you to pick up what the audience loved after a respite. But, in the more common case, you’re getting a second chance to attack that game in a way we didn’t before.

In class, what we did was a version of the French Harold, which is itself a version of the Harold with no group games (French Harold is so named in allusion to the theatre term French Scenes, meaning scenes separated by characters entrances and exits rather than lights or scene breaks….which we have so it’s poorly named, a French Harold would be a Monoscene to me).

Our version The Harry (and it is out version, if you have a better name feel free to suggest one), is a further bastardised Harold (therefore perhaps the most french version of all) where we chop off the group scenes, the opening, as well as the final beat.

The scraps you then serve as much as you like, over and over to challenge yourself in wringing out the game (it is similar to a format called French Braid, the french moniquer a coincidence, where like the hair style three scenes intertwine forever). The first scenes might still be trying to lock The Game down, but by the second round we should be solid.

Anyhow, that’s The Harry. 123, 123, 123 forever. Or until you collapse in a wet pile.

I doubt it’ll ever become a show-format, rather than a class drill, but there you go.

The Harry.

Solo Practice

Really? You’re…still keen?

In a World: Ask yourself, in a world where BLANK WEIRD THING, what would the world be like? For instance, in a world where birds use power tools. Write ten examples of the impact of this weird thing, as stretching the premise as that would be. Try to make them as seperate as you can.

Then, choose one (or a new weird world and consequence altogether) and then ask If This Then What. What would also be true, if that were true. Consequence of the consequence.

Then, ask If This Then What about THAT consequence. Go to town again, really push it. If possible, try to have the consequences only connected by a degree of one ie A goes with B, and B goes with C, but A and C have no connection. Your consequences can be historical, fictional (from pop culture), dire, minor, philosophical, taken from your real life, or all of them alternating to keep it fresh.

Tai Chi: This one is more time consuming, and full on, but the results are way better: take existing premises on a sketch show, and write a sequel with those characters. This might be raising the stakes, or just adding more jokes. Try to keep it as realistic as you can ie you could see this sketch being on that show. Stick to the show’s voice if you can, but if you need to make it your own that’s fine and encouraged but KEEP THEIR GAME. This is good for Time-Dash practice

Then, pick another sketch and write a rip off of that sketch. Just take their premise, change the specifics enough you won’t get caught. For example, the Dead Parrot sketch becomes the worse Terrible Food sketch, and then becomes the Annoying Personality sketch. This is good for Analogous practice.

Now finally, write a sketch that has nothing to do with any of these sketches. You can take an element like a prop or location or word if you must but otherwise make it as original as possible, and very very funny. This is good for Creating a Great Sketch.

Enjoy

Damn I’m hungry