Lesson Beta: SCENE TYPES

The second in my boring lectures about improv from my 2016 class.

Introduction

Today we are discussing scene types. By types I don’t mean different formats, but the fundamental heart of scenes. So think of them as different personality types than different occupations, maybe.

Yeah, that sounds good.

Now, despite my analogy of the heart of scenes, this is a reasonably heady topic at the beginning. It is asking you to analyze a scene and create a diagnosis and a prognosis instantly. You also have to do it as a scene is starting (as is the nature of improv), but please do not panic: today we are just going to analyze the scenes. The implementation I promise will just come, the practice comes with practice. In any case, the scene-start topic is one for another day.

Second disclaimer: no this won’t ruin improv or comedy forever, chill.

The Four Primary Colours

There are many thoughts on the different scene ‘types’ (I am quite partial to Joe Bill’s simple ‘two folks fighting, or two folks fucking’).

But I was trained by Miles Stroth, and his definitions are relatively straight forward, and to the best of my research they don’t break other people’s theories (I have considered UCB, IO, IO West, Annoyance, Bad Dog, New Movement, Westside, HUGE, the little I know of Rapid Fire, and Groundlings) so we’ll go with that. It’s a fair starting point anyway, feel free to investigate further. He stresses he didn’t come up with these scene types, he just codified them. These scene types are older than the hills, and go beyond improv into comedy DNA (which is handy, as its easier to give examples from written sketches as these are more wildly available). This isn’t comedy maths, its comedy truth. Miles Stroth is a cool dude is what I’m saying.

All that said however, as cool as Miles is, I have my own opinions about some of these types and speak these opinions freely. Grain of salt as always.

His four scene types are Realistic, Alternate Reality, Straight/Absurd and Shared Perspective.

Realistic

(also called Normal, also called Slice of Life)

Realistic is as it sounds, a moment on stage as if the real world. You talk as yourself, with someone else talking as themselves. It’s a conversation really. It need not be funny, which can trip a lot of improvisers up. Top of your intelligence is important here.

I really don’t see much of this. Maybe TJ and Dave a little, Jimmy Carrane, there is probably other’s in the slow comedy set?

I do however see it plenty when hosting a show, and in stand up’s. It’s banter, and you probably see elements of it in dramatic improv. People playing and being funny, rather than playing at being funny people.

Importantly, it’s a great place to start your scene. Entering a scene assuming its realistic will mean the base reality is strong and fertile, ready for the seed of unusual thing (much easier to spot against that plain background fo realism) will grow into a weirdo ugly flower of absurdity. You might transition into another scene type very quickly, but even a slow burn scene can be very satisfying to an audience. If unsure, build a floor.

Alternate Reality

(also called Shared World)

Alternate reality is a realistic scene, but one major thing has changed and everyone is cool with it. Vampires suck cola not blood, money is bunnies, what is Halloween like in the Harry Potter universe, whatever. Maybe you have a scene where a medieval minstrel played The Globe Theatre as if it was a rock concert (complete with screaming fans and calls for their old stuff and throwing armour underwear on stage). The whole world is absurd, including these characters, and we are walking through the repercussions. If this is true, what else is true?

Any time you are following the plot of a movie or existing known world, there is a good chance it is Alternate Reality. The Movie form is often alternate reality. Most forms of satire or parody are alternate reality. If you’re ever unsure what scene you’re in, there’s a good chance it’s this one. It’s a real whole-ensemble run of scenes.

Now, this might not seem very clear just yet, because I think it’s easier to explain once you know the other scene types.

Let’s see an example from That Mitchell and Webb Look

I have explained these two first for two main reasons.

- Frankly, they don’t come up all that much (although Shared World might come up more as a second beat come to think of it), so I rather get them out the way.

- I personally believe they are actually subservient to the other two scene types.

Shared Perspective

(also called Character based scene, also called Peas in a Pod, also called Double Absurd, also called a Gaggle, also Two Folks Fucking)

Two characters share a point of view (‘kids today have no respect’, or ‘there’s a lot of hot babes in this club’). They may dress alike, sound alike, say things alike, the important thing is they agree, and are waxing lyrical about that agreement.

Examples

- The Fast Show is full of these guys: the suits you guys, the fat and sweaty coppers, the pissed family.

- Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum.

- Dumb and Dumber.

- Deedle Dumber and Dumpty Dumb

- Absolutely Fabulous.

- The Management (Hale and Pace).

- Hanz and Franz.

- Dick in a Box.

- Blues Brother’s.

- The Dangerous Brothers

- The Ritz Brothers

- Dodgy Brothers

- Marx Brothers (to an extent)

A lot of brothers now you mention it.

The way Miles teaches it, it is an exercise in energy feeding, two positive forces feeding off each other and growing to supernova level. In the Key and Peele sketch about the doormen who love action films (“that would be my shit!”), they yes and each other so hard the scene ends with them literally exploding from enthusiasm.

You reflect and enhance mannerism, the voice, the body, the mantra (or catchphrase, very common with these scenes: it acts as a line break, a unifier, and works best if ironically or not sums up their attitude to life ie Bill and Ted’s ‘excellent’, Bill and Ted rip-offs Wayne and Garth ‘shwing’ or ‘party on’, Statler and Waldorf from the Muppets laugh, Banana’s in Pyjamas ‘are you thinking what I’m thinking B1’ and ‘me go in-sane for the co-caine’).

Repetition is also a key factor to these characters: there is a reason why they are often recurring characters. Within one scene, you’re going to hit your mantra a few times.

Let’s take a look at one. This is from A Bit of Fry and Laurie

Note the use of mantra, and how their agreement comes through even as they shout.

These scenes are often fast and furious (although not necessarily, Waiting for Godot goes for a while): hit it, hit it harder, hit harder,, hit it harder, leave them breathless. The shared perspective scene is a fast starter and a big ender (on a repeated mantra), so it’s a great scene to assume your starting because mirroring your partner’s attitude offer feels good and supported and dynamic. It’s a scene nose to tail built on Yes And, you’re literally saying yes a bunch, and therefore its improv pure.

So what are some of the pitfalls? A lot of new improvisers will panic in these scenes, because you gotta go big and feel like a doofus doing it. It helps you’ve got another doofus with you, but it’s still a big call.

I think it helps not making eye contact as much, because the you see the blind panic behind the energy (that is a good tip for any absurd character, they often look outwards, they are presentational by nature). The bigger problem a lot of folk find is a big character won’t automatically hit straight away, but Miles insists you just gotta go bigger, repeat more, high energy high reap. It’s funny on the 5th repeat of the mantra. Another pitfall you can fall in is feeling there’s not a lot to do: no conflict. The solution, I feel, is to direct your anger/conflict/interests outwards. To other people, to the world, you are united in your passion (as I said, looking out the audience).

Let’s look at some examples of these latter type

This is a sketch by the group Choir

Notice how they direct their frustrations, anger, conflict, not to each other and but outwards. Also note their mantra ‘sisters in law’.

This is Confessions of a Tooth Fairy by a very young Kristen Wiig at The Groundlings (Kristen Wiig and The Groundlings love this type of scene over there)

Notice the two fairies differ in their methods, but are unified by their worry they’re bad fairies. Also note the mantra ‘the money’.

Another method to keep the scene moving is to turn that Yes Anding and heightening more sinister, more competitive. So even though two people are in conflict, they agree with each other’s perspectives completely. Well I say two, this sketch actually does this with four shared perspective characters. It is one of the great sketches, the Four Yorkshiremen sketch.

Notice the mantra, subtler here, is the equivalent of ‘luxury’ or ‘paradise’ as a rejoinder. Also note that despite the contest, they came together in the end.

Here is one with TWO sets of shared perspectives characters (each pair has their own perspective, but the quartet also share a perspective), one set named after a THIRD famous shared-perspective set of characters. Masterclass, am I right guys?

Now like a lot of these sketches, the characters dress and sound similar. But it’s not always needed, if they share the perspective. It’s sometimes called peas in a pod, which is a good analogy. I personally call them fruit in a bowl, character linked but still separate in their own way. Perhaps a good example is Smashy and Nicey

I find this more visually interesting, for one, and it also allows a greater variety of comedic lines or choices within your theme (Mad Hatter and March Hare). I also think it’s simply more authentic to the improv experience: as much as you Yes And your partner, your own voice and choices will still come through.

Shared World to me is under the umbrella of Shared Perspective

Now, if I’m honest, often this scene type can leave me a little cold. When it works it really works, but I’m less a character guy to start with so a double dose is not always a tasty meal.

It’s usually comedy actors who like crazy people in sane situations, and writers who like sane people in crazy situations.

- Robert Smigel (writer SNL, head writer Late night with Conan O’Brien)

I guess we just all gotta get along. Which leads us to the final type, and my favourite.

The Straight/Absurd scene (two folks fighting)

The cornerstone, in my opinion, of basically all comedy. One person has a single weird kink, the other tries their hardest to fix this kink.

The straight is our audience surrogate. This audience surrogacy is something I make a big deal about: the audience has to know what is strange, and what is normal. You can do this with grounding in all its various forms, having recognizable scenarios you are subverting. An advert parody often has an in built audience surrogate, because we know how it’s meant to go, and deviations from the norm are obvious.

But when it’s less obvious, the easiest, and often the most effective audience surrogate is the straight man/ absurd man dynamic.

The straight man* is the person we the audience identify with.

* I say man, obviously it can be a woman. Woman play straight man in almost every sitcom of the last 30 years, Home Improvement, King of Queens, Everybody Loves Raymond, Coupling, Mork and Mindy, even workplace sitcoms like The Office, Newsradio, Scrubs, Black Books, even in female lead sitcoms like 30 Rock, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and Parks and Recreation (particularly Anne, the protagonist). Interestingly, before that it was usually the woman who was the absurd character (Goodman and Ace, Lunt and Fontanne, I Dream of Jeanie, Burns and Allen, I Love Lucy). The straight and absurd doesn’t even need be human, or traditionally sentient: a paintbrush and a germ will do fine.

Now I’ll just talk semantics here for a second, because I think its revealing. We will see.

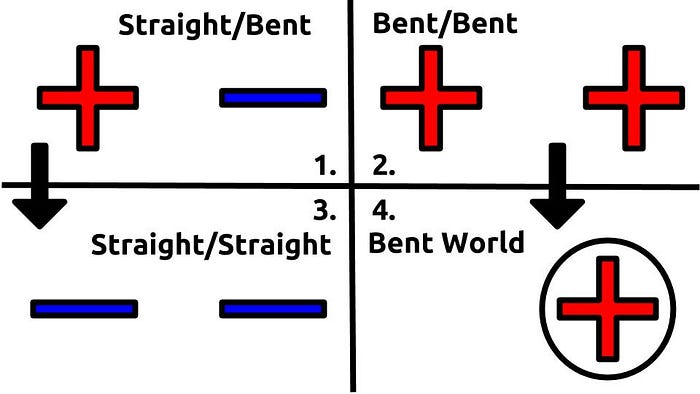

The absurd is sometimes called the crazy, and the straight is called the voice of reason. I prefer the term straight and bent. These aren’t perfect, for obvious sociopolitical reasons, but to me it better illustrates the dynamic.

Here is the straight man, straight and true.

They are proud of their straightness. They define themselves by their straightness.

Now there may be a perception of the absurd man looking like this

Crazy, a line going all over the shop. But this bloke is just a ball of random. It’s not funny, its annoying. Its hard to play against, and very hard to laugh with.

To me, the absurd is only absurd about one little thing, however deep that runs. They are the same as the straight, but slightly bent. A kink.

As you can see, they are apart now, but soon they are destined to intersect, to clash, if they continue their path. And both characters insist on continuing their path (the bent blissfully, and the straight stubbornly).

The real crazy one is the straight man, who thinks he can change someone’s fundamental nature with words alone. If you take the old definition of insanity as trying to do something the same way over and over, expecting different results, then the straight man is bonkers. The bent character is not simply ‘crazy’, doing any Dada dumb thing that comes to mind. The straight is using ‘reason’, but often is being unreasonably affected by the shenanigans. In the Dead Parrot sketch, Michael Palin refuses to admit the parrot is dead. He doesn’t also throw his poo around. If he did, it would be the Throws His Poo Around sketch. Now, if he throws his poo around because he refuses to admit the parrot is dead, we might have something, but he doesn’t so we don’t.

The straight is a line, the bent is a bent line. Eventually they are going to intersect, clash, and we are watching that moment. The more bent the bent, the angrier the straight because that was totally your fault you crashed. Slightly bent, well he’s just trying to nudge you back over your side, he sees you coming.

The straight person pushes against the absurd thing, ‘frames’ it with normality. It is not simply recognizing the absurd thing, or just trying to stop it in real life. When we say call out the absurdity, we don’t mean simply pointing it out, it’s calling out as in to challenge.

You are showing it not just be shining a light on it, but spotlighting, highlighting, finding the light the shows it off best.

For advice we turn to famous comedic scholar, Ice Cube.

The straight man is valuable, not conflict with the comedian, but to enhance what he does

– Ice Cube, on the set of Ride Along

Don’t be fooled though, that’s you the improviser. Your straight character, however you slice it, simply doesn’t approve of the absurdity. So why don’t they just leave the scene?

For the reasons you probably already know.

1. Relationship: If they are invested, they are more likely to stay.

2. Ego: They have to be right

3. Circumstance dictates: Lost a sea, space, handcuffed, status etc

4. Curiosity: It can kill a cat. The straight man can’t help but want to know more.

5. He is willing to be convinced: They really listen, they want their logic to be sated.

6. Want: They have a simple underlying deep want

This last point, a want, is the big one. It can include any and all of the others above although often it’s on its own: the straight person has a ‘normality’ they want to restore, often involving them achieving a Want or task, and they will work their straight little butt off to get it. This Want is usually very simple: Steve Martin in Planes, Trains and Automobiles for instance just wants to go home. Dorothy wants to get to Kansas, Alice wants to get to that terrible garden soiree. This Want clouds their judgment. If anyone is crazy, it’s the Straight, for thinking that this Want can change the fundamental nature of the bent.

The Bent character also often has a Want, although it might be safer to call it a drive: a drive to do their ‘thing’ all day long. They love it. This is a drive is fueled by that bend in their line, their little kink, and it is that kink that informs their lives. It is the rose coloured glasses they view the world in. Paul Vaillancourt calls it their hammer, and like the saying goes they view every problem as a nail.

One final diagram to illustrate.

The bottom line represents the base reality of the scene, the platform, the environment. The normal world of the scene. Since this is straight/bent and not alternate reality, this normal world is considered normal by us the audience. The straight man is a direct product of this normal environment. From it he grows straight and true. Like dry spaghetti, he can only be one shape. The bent is coming at him, and in response he strays straight. He cannot break, because then he will no longer by part of the environment, and that is all he knows. Every time the bent tries to convince him to bend, he only need look at the environment as an example of that’s not what to be. This looking might be towards to the audience (he is our surrogate). It might be to literally talk about the environment, the ‘normal’ world and how the bent violates it.

And it’s as easy as that. The bent is always trying to do their thing, and the straight hates it (often because it directly impacts on his ability to function).

There’s the look of concern, like, trying to figure you out. Like what are you? Are you actually human…whatever they give me, I probably have a look to counter it…I look like what the audience is thinking

– Ice Cube, during the filming of Next Friday

Counter is the right word. Blocking each shot, showing its impact, allows us to see its effect. Crazy Town isn’t bad because it’s full of crazy things happening, it’s bad because it’s got nothing happening, just crazy spinning like a crazy cog without teeth. The straight man and the bent man work in tandem, Ying and Yang, their energies always responding to each other.

Soap Box

Here is a big point I want to make today: it is often said that the straight character is the boring character. It is not. But I’m not surprised that’s the view.

In early double act vaudeville, this straight/bent dynamic was often this:

Straight character: Ordinary line to the audience

Bent character: Funny line subverting that ordinary line.

Straight character rolls his eyes.

This was so ingrained that the bent character was often called the comic character, and the straightman (the actor) would get 60% of the gross and top billing for doing the ‘shit work’. Often the guest star on a comedy sketch show, without a funny bone in their body, will act as straight person because they only need to feed lines.

And that’s cool! That’ll do! But that is but one kind, and not indicative of what came before, or after.

Even if you take that model, in improv we don’t have feedlines and jokes in the same way, so coming up with organic straight lines to keep the scene on track is hard enough. And obviously just because you are not getting the laughs doesn’t mean you aren’t creating the laughs, it’s an ensemble.

But even beyond that, the funniest person on stage can be the straight guy. And for my money, they usually are. Carl Reiner played a straight guy. Albert Brooks played the straight guy (Brooks connection accidental). Jack Benny, Jason Bateman, Martin Freeman, David Mitchell. The straight man’s so funny, Shelley Berman (of the Compass Players, factoid) and Bob Newhart did routines with only them! Buster Keaton played straight man to nature without dialogue! Often the straight guy, for instance, is the one pointing out the funny anyhow.

Comedians might think they are best for the ‘funny’ character, but with their observational incisional chops they often make great straight people. Actors might think they’re suited for the big characters, but with their human grounding they make great straight people. Some people say ‘I like improv/ I like comedy, but I don’t think I’m very funny’. Good. If you have good comedic taste you can be a straight man, once you recognize that comedic thing, all you need to do as James Cagney says “Find your mark, look ’em in the eye and tell ’em the truth”.

So straight-manning is an anyone role. It’s literally the everyman! As such, there is a huge variety of straight character types, so feel free to experiment with what works for your piece. When we think of ‘characters’, we think the bent character, but that’s not the whole story. A Groundlings sketch will often have one bent character, and a whole location full of straight characters. A UCB sketch will be one to one, and usually intellectual equals. I personally prefer one straight person, and a whole world of absurd: the Alice in Wonderland if you will (I am using this analogy a lot I know). An extreme version of the world against you is one straight man, alone, battling an unseen bent world. Over and over again, I will laugh at this scenario.

Let’s look at a couple of straight character types

1. Be As Dry As Toast (improviser type: Joe Wengart): Just adopt a reasonable, moderate tone and engage the insanity with a disarming voice of reason, or sometimes deep knowledge (Chad Carter). This is not your first rodeo. Of course, we say disarming, the bent is never disarmed. OR

2. Have Just A Small Stick Up Your Rear (Neil Casey). Be perturbed, prissy and put off by the crazy person. Both the straight person and the bent person can be arrogant idiots. This can also be the villain of the movie, which is odd to think about the character the audience relates to isn’t who we are rooting for. OR

3. Be Insanely Freaked Out (John Gemberling): Be completely taken apart by the craziness! Scream! This is the nuttiest idea you have ever heard of! This will ruin everything! OR

4. Walking Through a Spider-web of Politeness (Jack McBrayer): The other person is bonkers, but you really don’t want to be the one to say it. Tie yourself in knots trying to spare their feelings, and tip toe around to reason. A light touch, a lot of “….right, well…yes I see what you mean, but….well”.

Similar to….

5. Want to Buy a Ticket (Tim Kazurinsky): be really rooting for the bent to be correct, but the further you go, the worse the road becomes. This is especially useful when if they’re right you benefit, or you are trapped and just want it to be better. The straight character can be a touch stupid here, if you like, but not as much as…

6. Straight Savant (Derrick Flores): Point out all the logical fallacies, but are too dumb to realise. Follow blindly the bent. Satisfy the audience’s need for sanity. Can sometimes lead or cause….

7. Hoisted by own Petard (Heather Anne Campbell, sometimes): Started off blind to the absurdity, perhaps their own, perhaps because the buy in was too great, but has seen the error of his actions. Tries desperately to reverse the decision, but it’s too late, or they have too much to lose. Might be reduced to Homer Simpson’s screams.

8. Normal Frustrated Joe, Trying to Get By (Ian Roberts): Just…can you fix my car, or not? Hey, where are you going with my pants, what’s that got to do with anything! Isn’t pretending to be an expert, but this is definitely not right.

9. Straight up Laugh in your Face (Aaron Jackson): The ‘oh my gaaaawd’ variety. They find this straight up ridiculous, and are unafraid of the consequences. Dean Martin and that generation of feedline-straight men reminds me of this, as far as the fun side goes. Let your genuine enjoyment of the sketch fuel your energy.

The list goes on and on. You can run the gambit of emotions, or even-keeled. You could be like Daria (jaded and unaffected)or Daria’s father (wound up on the edge of breaking down). Winnie the Pooh is befuddled and Eeyore is world weary to the point they are often comedic characters.

The Simpsons has one of the highest concentrations of idiots this side of Dibley, but also its share of straight characters. Lisa is a different straight person to Marge, in turn from Krusty, in turn from Smithers, in turn from Flanders. Each of those characters have their own straight relationship (Marge to Ruth Powers, Krusty to Sideshow Mel, Smithers to Stacy Lovell, and Flanders to Reverend Lovejoy). On top of that, Lisa can be a different straight person from scene to scene; the vegetarian side might come out, or the intellectual side, or the little girl side. Any of these sides might be around Homer, depending on plot.

Adam Sandler when he straight man’s is often juvenile and cocky, a loser made good. As he’s aged, the juvenile side has shifted slightly to a more world weary working class, but the ‘simple things’ side remains firmly at the core. David Spade is catty and sarcastic. Ben Stiller is straight against characters played super straight, aggressively insisting they’re sane (played by serious actors like Robert Deniro and Dustin Hoffman). They make his seem crazy, milking cats and what not.

The straight person can be the sweetest person in the world, only trying to get by. Moleman from the Simpsons. The straight person can be a proper villain, like Shooter from Happy Gilmore (that’s right, the villain and the hero take it in turns being straight). Or a bit of a mix, like Daffy Duck (who despite the name, is no longer very daffy).

The straight person might even be a bonkers character on the surface, a half robot half Falkor, crazy every day of the week except right now. It’s about their view in this one snapshot in time.

The bent and the straight might completely talk as equals (if it gets too close to real life i.e you the improviser talking, it becomes Normal which I consider under the umbrella of Straight/Bent. Please note just because something played natural, doesn’t mean it’s not strictly straight/bent with a big flapping weird premise).

The straight person, as I’ve mentioned, might even be identical in every other way to the bent person ie peas in a pod, except for that one non-united aspect of attitude or POV. Two talking pieces of horse shit can disagree.

You have so many choices for this very needed character, but I will stress: since you won’t have much time in a sketch you are probably best to pick one type and remain consistent. I mentioned how certain characters can be straight and bent? For instance, The Marx Brothers have a hierarchy of straight: Zeppo (or Dorothy Lamour) is straight to them all, Groucho is straight to Harpo and Chico, Chico is straight to Harpo, and Harpo I guess was confused by a dog once. Well, that’s over the course of several movies, or a 32 season sitcom, or at least an episode. In 2–4 minutes? Harder. Not impossible, but harder.

My golden rule is this: a scene gets one tilt where everything you thought was true is recontextualized. Likewise, a scene type can shift once. If it shifts again, it was because we were tricking you the whole time with that shift and it goes back to its original. I can’t think of a scene that ran three scene types successfully, and I’ve seen hundreds fail. If it can be done, save it for a sketch.

What you CAN change as the scene progresses, what you the straight character always have control over, is your emotion. A skeptical straight can become even more so, a police straight can be pushed to their limits etc. Alternatively, you can let emotion shift your straight character completely from on type to another, based on their emotion and despair.

Perhaps a demonstration is in order? Here is one of the great straight men, Kermit the Frog

This is a tightly screwed on jar popping under the pressure. His pot bubbles over.

Alright alright, there are many types of straight man, stop talking about it

I refuse

It is in a straight character’s nature to be strung along, but the bent character has to help. They have to provide hope, a glimmer of light that maybe they can be reached. This is another reason why crazy is a terrible description, because who wants to engage with a crazy person? They have nothing to give, and getting something (and loyalty/shame) are the two best incentives.

A dirty simple way of doing this is “Punch, Punch, Pull Back, Punch”. That is, you

1. Hit the straight person with the bent thing,

They question it

2. You hit them again.

They are now convinced you’re forever bent, they go to give up on you.

3. You pull back and give them a glimmer of hope you’re not crazy. Maybe the straight has something to gain, whether as grand as treasure or as simple as they won they argument or their transaction can commence.

They come back, thinking you’ve changed.

4. You punch them again, harder. You will never change.

Does this make sense? Let’s see a shit example

Dave: I know I owe you money, I am going to pay you back in sand instead

Daisy: …I don’t want sand, why would I want sand?

Dave: Because you can make things out of sand.

Daisy: Well you can buy things with money, please give me money. If you can’t give money, I will report you to the small claims court.

Dave: Fine fine, I understand. Here, take this stack of money, with interest

Daisy: Thank you, I appreciate that, it’s just I need that money for rent and…this is sand

Dave: I made the money out of sand

Punch, punch, pull back, punch. Hope is given, and taken away.

Also, while we’re at it, I’ll point out a few other things. The straight character asks questions (this was also a transaction scene, and definitely a kind of argument, we’re breaking all the rules baby). If I was writing longer, as in more dialogue in shorter bursts, I would have a whole lot more questions. This is natural! Of course the straight character has questions about this sand bartering system, you would too! If your partner says something you don’t understand and you don’t question it, you aren’t really listening to them at all, you aren’t fully Yessing their idea! It is also OK, and encouraged, for you to load your questions with the answer in them i.e “what’s so valuable about sand? Are you talking about a special sand that has become a diamond, or…or something?”. The straight character is searching for answers of course they are going to try and answer them for you and return to their normality. But the thing about straight character, they more they dig the deeper they go, never satisfied.

The straight character in that scene snippet straight out offered more unusual thing for the bent person to have done. Because you are are both improvising here, and helping each other to help the scene.

The straight man is sometimes called the support player, and I’m happy for this to be so, because I like getting praise. I think you could argue any element of improv is supportive, we are all supporting a scene. But yes, straight characters are being supportive, while on the surface trying to take away support. By engaging, their engage the bent character. Their actions to quell are what stokes the fire. To use a metaphor I haven’t fully thought through, the game of the scene is the engine of the bent man’s car, keeping it moving, and the straight man is the road, always present, always offering more, always getting run right over.

I won’t go too deep into how a bent character should act, as that is a whole separate topic (see: Game). But some good rules are

1. Be enthusiastic: You can decide the level, but it is acceptable to be high on the supply. Your enthusiasm has to survive the onslaught of questioning from the straight character. It’s a balance. If you let it get you down, you will bum the audience out (if the straight character doesn’t also adjust and be kinder). Some bent characters will argue back, some will remain blissfully unaware (Miles Stroth goes so far as saying the bent character should be looking out into the audience). Keep in mind, it usually means an upbeat positive enthusiasm, but it can also be negative i.e. you are enthusiastically passionately despairing and missing the point still. Enthusiasm will also propel you to keep hitting that unusual thing, and it will also give the straight person something new to obsess over, keep the danger in the air, keep annoying their itch. Enthusiastic people are also a person that invites discussion, which is good for a straight character who has a lot they want to discuss.

2. Be a little simple: You have your thing, and you just love your thing. The logic isn’t quite working for you. But please don’t be dumb: you thinking ‘the policeman’s flashing lights were a celebration of how fast you were going’ is simple, you ‘not hearing the policeman shouting because you sometimes forget how to hear things’ is dumb. It’s a new weird thing, and so belongs in a different scene. Being a little simple also invites a straight character to keep trying to explain things, instead of just dismissing you as an asshole (by the way, your unusual thing can be that you’re an asshole and you shouldn’t be, but you have to have that hope for change).

3. Be certain. You are as convinced you are right as we the audience are that you’re wrong, and much more convinced than the straight character is. You can appear to waver, but the unsinkable ship that is your quirk must always right itself.

4. Always come back to your thing. That’s come back, meaning sometimes it looks like you’re moving away…. but you always come back. It makes it clearer for you, clearer for the audience, and clearer for your partner the straight character. And it is satisfying, oh boy is it.

5. Always come back to your thing. It shows the importance of this thing, it shows how intertwined it is to the bent character’s fundamental nature, and it’s just funny.

6. Be active: this is related to the others, sure, but it’s worth separating. Just like how the straight character can’t leave it well enough alone, neither can you. You keep providing weirdness to bounce off. You use the environment. You use your history. You make active bold choices, and these choices are all informed by your weird little kink.

7. Right when they think you’ve moved on, always come back to your thing.

So that’s the bent character, for now

Would you like some more tips to be a straight man? No? Too bad!

1. Point Out the Funniest Dumb Consequences: Especially if we the audience go ‘oh yeah’. Note I (well, in this case, Will Hines) say consequences here, not just the dumb things already happening. You should point out the dumb things too, but just not that alone. For example ‘sand is not money’ is good, ‘Even if sand valuable to you, its not valuable to anyone else, which defeats the purpose or currency’ or ‘where would I even store all that sand’ or ‘if you like sand so much, stop borrowing money off of me, I will give you sand for free’ or ‘I am sick of getting sand from you. My house is full of your sand gifts. It is impossible to keep tidy, you can’t clean dirt’

2. Challenge Them: Come at it from every angle. It’ll only give you and them something new to bounce off.

3. If You’re Ever “Winning,” Back Off: You’re the hero of the story, the everyman, but you’re going to lose. We love to see ourselves lose. That punch punch pull back punch is still punches. Regardless of your tone, you will STILL be ALMOST CONVINCED, you will still be CURIOUS, you will REMAIN ENGAGED and CHANGEABLE.

4. Try to explain, but never get to the bottom of it: It’s also good to provide the bent character with reasons for their behavior, to provide their motivation. Just be sure not to explain away the fun. Easier said than done, I know, but worse comes to worse just have the bent character remain bent even after all that. Punch Punch Pull-Back Punch.

5. Always come back to your thing. Yes, you have a thing too. Whatever this joker is getting in the way of.

Now, to emphasize a point I made before, just in case it got buried in all that palaver: A mistake, when it’s not a choice, is to let your straight man be simply a naysayer. Give every character a backstory, or at least a POV, including your straight man. The straight man wants something, and it’s related but not only getting the bent to curb their ways.

The straight man and the absurd man both think they are right, and both think they have the power, if not the upper hand.

The straight man gets nowhere from his anger, and gets somewhere he doesn’t want to be from his compromise and peace offering

The straight man can’t help but try to make sense of his world. Every try makes him deeper. He discovers alright, but at what cost?

It might seem like the straight character is a wall for the bent character to bounce off of. Steady, unrelenting, reliable. Always saying no. And that’s true of many scenes. But often the straight character is actually the ball, trying every angle, never getting through. The straight man is not a passive role, it is dynamic and creative.

In summary

(thank fuck for that)

• Audience surrogacy: what is normal? This is often what your scene explores.

• Fruit in a bowl: they have differences on the surface, but they are both fruit and therefore think like fruit, and therefore have the some POV from that bowl.

• The straight man has a want. This want can never be sated.

• The bent character has a hammer. Everything’s a nail.

• If in doubt, call it out. Better to be obvious then lose the audience.

• Just when everyone has forgotten it, always come back to your thing.

And finally, a quick dumb rule for deciding what the scene type it is.

If they say You or I, it’s straight/bent probably. If they say We, it could be fruit in a bowl if you like (unless you disagree with them from the out, and that might change as other things come up).

At the start of a scene, when in doubt, Yes And hard and run closer to be fruit in a bowl then straight/bent, Like I said, you can always find and dwell on that point of difference later. A straight character can still have the skin and mannerisms of a bent, be cut from the same cloth. This actually make it more likely he will try to talk sense into the other, he relates, he wants to relate more. It’s generally just polite to just act according to the base reality you’re being given. Will Hines calls this the in-bound pass, the handshake, it’s just getting the game started, don’t try scoring points just yet. Besides, we will be dwelling on this way more in a few lessons.

Super heady and a little confusing tip to end on, despite never mentioning that stuff in the previous four thousand words? What can I say?

Less.

Bonus Section

Here I try to answer some questions that have come up since publishing

Someone comes on as an absurd character. How do I know whether to play it straight (straight/bent), or be an absurd character too (fruit in a bowl)?

It’s a good question. The answer comes from James Mastraieni

Personally I believe that it’s easier to two peas in a pod when the premise or idea is less unusual or absurd and more based in character specifics or an emotion. If I can use an adjective to describe the two characters together then I feel comfortable going two peas in a pod. The example I’ve been using this week is if in the opening somebody uses the phrase “sassy old men” and somebody initiates a scene clearly playing a sassy old man on a porch it might be more fun to play into that idea than try and straight man it. (BTW I’m not the best two peas in a pod improviser so this advice may be garbage.)

On the other end though if somebody sets up a hard context and then drops an unusual specific in that context making it seem pretty weird than it may need a straight man. For example if somebody initiated, “So the reason I’m interviewing for this job at this retirement home is I’m trying to hang out with more sassy old men.” It feels stronger to me to straight man this line given the strong context and the fact that most interviewers would be pretty put off by that sentence.

So essentially I think when you’re trying to decide whether to straight man or two peas in a pod listen closely to the initiation and if it’s more unusual then straight man, if it’s less unusual and more based in a character trait or emotion then I think you can two peas in a pod it.

Thanks James.

Here is Miles Stroth with the pocket version

If the character is bigger than the idea, you go character. If the idea is bigger than the character, you go straight absurd. — Miles Stroth (Pack Theater, The Family)

I will add a coda that there is no real right or wrong answer, and therefore i’s largely personal: what do you feel like doing. If you have an idea for peas in a pod, go for it. If you feel a straight character coming along, embrace it. Like James, I personally prefer a straight/bent. You might be different. I hope you are different, it’s a big world of improv out there.

The advantage of responding with a straight character is you can tread water a little until it’s clear what the unusual thing is. You are just reacting how a normal person would react, and it’s hard to go that wrong there (you can, of course, and I actually think premature straight manning has killed potential alternate reality scenes)

The advantage of responding with another absurd character is it’s easy enough to just copy the other person’s walk on character, boom, instant peas in a pod.

Pop Quiz

Identify each of these scene types

This one is from improv group Fuck That Shit

Answer: Plain old fruit in a bowl. Even though there is hostile tension throughout, they agree super hard. They even admit this by the end, becoming best friends.

This one is from Norwegian sketch show Øystein og meg

Answer: While there are elements of straight/absurd, with one character we clearly identify with over the other, I believe this to be shared world. They both accept the absurd difference from out world as normal, and the straighter character does treat the other’s absurd questions as unusual even if they aren’t questions he would ask

This one is from the Carol Burnett show

Answer: They begin very much in the world of shared-absurdity, but its quickly becomes a straight against a bent world with the roles doubled and sometimes directed towards each other.

This is from Mitchell and Webb again

I think this is Fruit in a Bowl (no pun intended), albeit a calmer version. They are also straight manning our previous expectations of characters, a joke used often not just in this recurring bit but in Mitchell and Webb (and College Humour) in general.

_____________________________________________________________

Activities: New Format — La Ronde

Named for the play The Round, the characters behave in a round. Easy? No.

A and B has a scene, B and C has a scene, C and D has a scene, D and A finishes it up. Then, has a montage at the end, with any characters interacting with any, it appears you can bring in new characters to interact with old characters. Need not have a running storyline, although it’s hardly a bad thing.

Variation: Do a LaRonde, second time around the previous player adds a ‘layer’ ie Shakespearean or serious or one person silent or one person has a deep secret never revealed.

Scenes are 20 to 50 seconds long. Remember all exist to each other so it’s possible although not necessary to be interconnected (some like Ty believe it helps if they’re all in the same location, giving them ties). When we played it the edit was called by walk out, but I think the tag works fine as well. Specifics in every character is super important, as you are going to have to follow that generic doctor to the next scene; it would help if he had a severe hatred of fish.

The LaRonde could be seen as an exercise in switching straight man: likely the character entering will be straight manning the first, then gradually has to switch to be weird themselves.

The entering person is not always responsible for the cut, they are responsible for the platform and their character. Remember remaining player to hold onto your character, and you may need a simple physicality or tic to jog their memory (especially if we montage later).

Solo activities

I mean….. Just watch comedy I guess, these scene types exist everywhere

Feel free to find your own, hopefully you do otherwise I’m full of shit.

A solo activity you can do is going onto one of these chatbot things, and try to have a scene. Be the straight, or be the co-absurd. Don’t try to get them to go straight, we don’t have the technology yet.

Look at those sketches. Think where could you put a related idea, in a new location. Why not try on different types of straight men for different scenes (the later the scene in the run, the usually higher annoyed the straight has to be, the quicker to judge)

But I guess you’d be hard pressed to find a better straight man than Bob Newhart. Here is a clip from one of his many sitcoms, where he exhibits a variety of different straight men (not all played by him) and bent characters.

Happy improv everyone. Any questions, please ask.